Relics of the Rebellion of 1837: the money vaults at Fort York

by Carl Benn

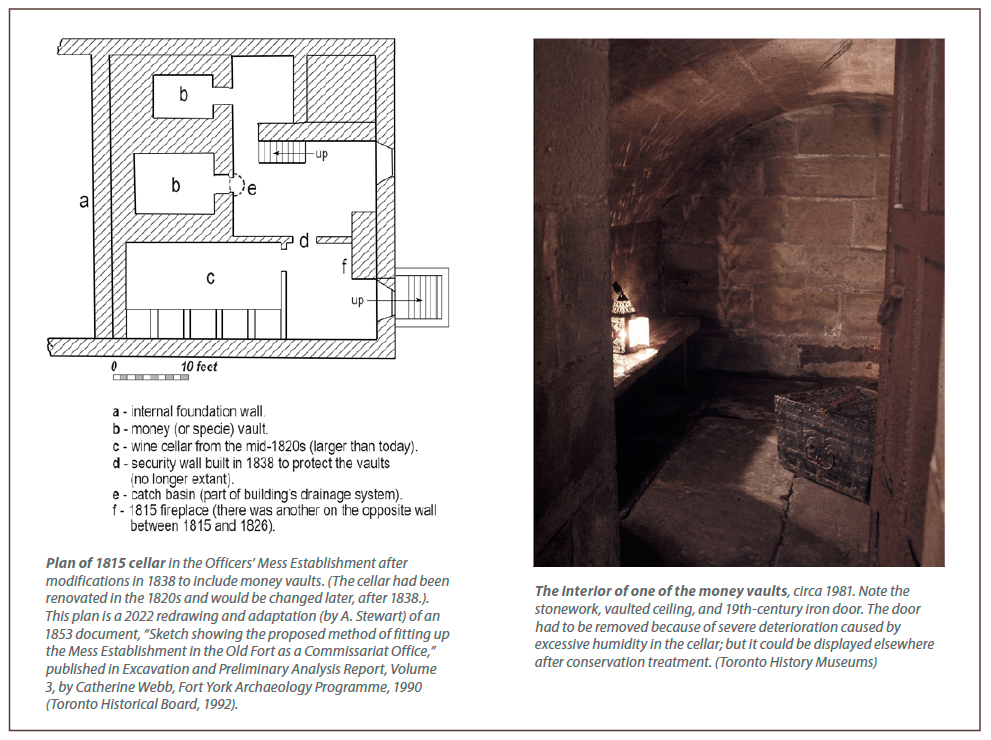

The Bank of Upper Canada on Adelaide St East at George St, circa 1859. (Toronto Public Libraries Digital Archive, Baldwin Collection of Canadiana, PICTURES-R-3103.)Two intriguing architectural relics stand in the Officers’ Brick Barracks and Mess Establishment at Fort York. They are dark, low, cellar rooms that many visitors mistakenly think are dungeons. Instead, they are specie, or money, vaults. They were installed at the end of 1838 to protect bank and army money from guerilla raids on Toronto during the tense aftermath of the Upper Canadian Rebellion.

The Bank of Upper Canada on Adelaide St East at George St, circa 1859. (Toronto Public Libraries Digital Archive, Baldwin Collection of Canadiana, PICTURES-R-3103.)Two intriguing architectural relics stand in the Officers’ Brick Barracks and Mess Establishment at Fort York. They are dark, low, cellar rooms that many visitors mistakenly think are dungeons. Instead, they are specie, or money, vaults. They were installed at the end of 1838 to protect bank and army money from guerilla raids on Toronto during the tense aftermath of the Upper Canadian Rebellion.

A year before, in December 1837, William Lyon Mackenzie marshalled supporters at Montgomery’s Tavern on Yonge Street north of today’s Eglinton Avenue. He intended to take the city, overthrow the government, capture Fort York, and set up a provisional government. Before he attacked, minor skirmishing occurred between his followers and government supporters on 4 December.

As Mackenzie prepared to march, loyalists in the city organized Toronto’s defences as best they could. They had little support from the British army because most soldiers in the province had been sent to Lower Canada where the threat of insurrection was worse. One of the major concerns for Toronto’s loyal citizens was the vast quantity of money in the banks. If the rebels robbed the banks, they not only could finance their cause, but they could threaten the province’s economic stability, already strained by the American financial panic of 1837.

The Bank of Upper Canada alone had £138,000 in gold and silver in its vault along with large quantities of negotiable paper. Loyalists, therefore, recruited a corps of “Toronto Bank Guards” and deployed some of them around the hastily-fortified bank on Duke (now Adelaide) Street, and positioned others at the Commercial Bank of the Midland District on King Street.

On 5 December, Mackenzie led 500-700 rebels down Yonge Street. Other rebels waited in the city, ready to join the rising upon their arrival. However, a small government force led by Sheriff William Jarvis ambushed Mackenzie near today’s Yonge and College streets and sent the rebels retreating back to Montgomery’s Tavern (and those in the city quietly stayed home). More skirmishing occurred on the Sixth. On the Seventh, one loyalist force beat off an assault at the Don River bridge while another dispersed the rebels at Montgomery’s Tavern in a short battle.

Mackenzie escaped to the United States where he attracted both Canadian and American supporters to his cause. These people launched a number of raids into Canada in 1838. Some of the attacks were serious, rivalling War of 1812 engagements. The gravity of the raids, combined with the crisis of the Lower Canadian Rebellion, kept Upper Canada on a wartime footing until the end of the decade.

Within days of the Yonge Street skirmishes, hundreds of loyal Canadian militiamen from the surrounding countryside moved into Fort York while others guarded key points around the city and harbour. The government restored the fort’s deteriorating War of 1812 defences, enlarged its harbour battery, and constructed blockhouses and other defences around the city perimeter. Meanwhile the British army reinforced Upper and Lower Canada substantially (and in the early 1840s replaced much of Fort York’s facilities with the “New Fort” in today’s Exhibition Place).

Yet, the security of bank and government money continued to trouble loyalists through 1838. The banks were a political as well as an economic target. Mackenzie had condemned the banks, describing them as “vile associations” controlled by the colony’s elite. In his denunciations, he singled out the Bank of Upper Canada because of its close association with the government. Mackenzie had gone so far as to promise that there would be no banks in his independent Upper Canada.

While loyalists worried, rebels made a dramatic foray into Upper Canada in November 1838. A force of 250 crossed the St. Lawrence River at Prescott. They hoped to capture Fort Wellington, cut communications between Upper and Lower Canada, and inspire a widespread uprising against the Crown. Once ashore, the invaders fortified themselves at a strong stone windmill a short distance from the fort. Hundreds of British regulars, Royal Marines, and Canadian militia – supported by steam-powered gunboats – counterattacked over several days before the invaders surrendered.

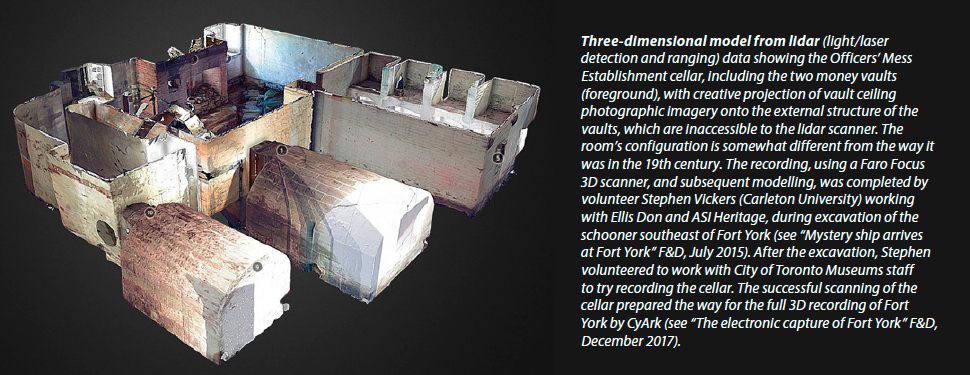

At the same time as the Prescott raid occurred, there were political assassinations in the Niagara area and rumours of invasion in southwestern Upper Canada. Fearful of a widespread uprising, the Bank Guards moved back into position after several months of inactivity. Nevertheless, this did not seem to be enough. The banks – and the army’s money at the Commissariat Office on Front Street – still were vulnerable. Therefore, officials decided to build two vaults inside heavily guarded Fort York as quickly as possible. One was constructed new for the banks. The other was dismantled from the Commissariat Office and reassembled in the fort. Both were located in the 1815 Officers’ Mess cellar. While construction went on in November and December 1838, a worried cashier of the Bank of Upper Canada, Thomas Ridout, sat barricaded inside his office, protected by the Bank Guards. If attacked, he hoped he would be able to hold out until troops from the fort came to his rescue. Ridout must have been relieved when the army finished the vaults towards the end of the year and transferred the money to the fort.

While construction went on in November and December 1838, a worried cashier of the Bank of Upper Canada, Thomas Ridout, sat barricaded inside his office, protected by the Bank Guards. If attacked, he hoped he would be able to hold out until troops from the fort came to his rescue. Ridout must have been relieved when the army finished the vaults towards the end of the year and transferred the money to the fort.

Both vaults were made of thick cut stone and had heavy iron doors to make them fireproof. To improve security, the army constructed a wall between the vaults and a (no-longer-extant) exterior door of the cellar as a second line of defence, and put a heavy lock on an interior door which connected the cellar to the ground floor of the Officers’ Mess. No doubt soldiers were deployed around the building in addition to the force that guarded the fort as a whole.

Eventually, tensions died down and the money vaults fell into disuse in the 1840s. ln the early 1850s, however, the army restored the vaults for the Commissariat, which took over the Officers’ Mess for an office. After the Commissariat left a few years later, the army tore down the security wall in the cellar, but the vaults survived, and may be seen by visitors to the fort today.

While not as romantic as dungeons at first glance, the vaults are fascinating because of their associations with one of the most dramatic periods in the city’s history, and, like many other treasures at Fort York, provide tangible and evocative links to Toronto’s complex past.

This is a revised version of an article Carl Benn wrote in 1995 while Curator of Military History for the Toronto Historical Board. He now is a history professor at Toronto Metropolitan University. We thank Allison Bain, Executive Director of Heritage Toronto, for granting permission to publish this revised version of an article that first appeared in Explore Historic Toronto (issue 8, spring/summer 1995), the newsletter of the Toronto Historical Board (now Heritage Toronto).