Joe Gill inspired and led The Friends over 25 years, helping preserve and revitalize Fort York during a time of massive change.

We lost one of our founding leaders this week. Joseph Gill died on 19 February at the age of 84.  Joe (left) with Fort York Executive Committee colleagues (l to r) Nancy Baines, Richard Dodds, Steve Otto and Geordie Beal, December 2007, in the Blue Barracks, Fort York National Historic Site. (photo by Andrew Stewart)

Joe (left) with Fort York Executive Committee colleagues (l to r) Nancy Baines, Richard Dodds, Steve Otto and Geordie Beal, December 2007, in the Blue Barracks, Fort York National Historic Site. (photo by Andrew Stewart)

Joe helped established The Friends of Fort York in 1996, which was registered that year as a charitable organization. Two groups of volunteers were brought together under the FoFY umbrella: one to support historical programming and interpretation, including the Fort York Guard; the other to monitor land use and development in the Bathurst/Strachan neighbourhood. Joe belonged to the first group and, on becoming chair of the Friends in 1997, was a leader in establishing the Fort York Festival (1997 and subsequent years). As The Friends grew, he helped unify and coordinate all its endeavours, serving as treasurer and as chair for many years. Joe has said that he thinks our greatest accomplishment, as an organization, has been to engage in precinct planning and development issues and to provide a critical appraisal of the City's own stewardship of Fort York National Historic Site and its precinct.

His interest in history started early in life, perhaps because his father taught history, as did Don Gibson’s father. He knew, following retirement as a partner at Ernst and Young (formerly Clarkson Gordon) in 1994, that his volunteer activities would focus on history. As a Chartered Accountant, he brought tremendous competence, financial skill and connections, as well as his personal passion for Fort York, to the new organization, which enabled The Friends to manage its affairs professionally and accomplish a great deal of charitable work in harmony with other individuals, agencies and the Fort’s owner, the City of Toronto.

Joe has been a tireless advocate and leader of efforts to restore programming to the Fort following elimination of the Fort York Guard from the City's budget. Joe led The Friends in fundraising for the Guard by running parking operations with volunteers during the CNE and other events. This resulted in a legacy of hundreds of thousands of dollars which continued to fund the Guard. Without this fund, and his careful stewardship of it, the Guard would not exist.

He truly championed and embodied a spirit of collegiality and optimism that prevailed at Fort York during the 1990s and early 2000s, when the fort was being sidelined in a changing landscape, especially during the years of municipal amalgamation and the loss of the Toronto Historical Board, which owned and operated Fort York before the City of Toronto subsumed Fort York and other sites into its new division, Economic Development and Culture.

Initiatives that will be remembered and identified closely with Joe are the considerable fundraising efforts he undertook and managed, together with his executive committee colleagues, on behalf of The Friends (donations, memberships, dinners and parking operations). He started up the period-themed Georgian Dinners, which were an annual fund-raiser for the Fort, playing on one of the strengths of the Fort as a centre of culinary history. He is also in large part responsible for the revival and expansion of the Fort York Guard. In partnership with the City of Toronto, we put 15-25 young people in uniform at a cost of $50,000 - $140,000 per year. The fundraising to do this each year and the ability to manage it with volunteers is astounding, in retrospect. Fort staff worked seamlessly with volunteers (FoFY) throughout this period to great effect, training, mentoring and presenting an outstanding, award-winning corps of paid university students each summer for over 25 years, since 1995, when FoFY first undertook to do this. The Guard's demonstrations of artillery firing, fife and drum music, drills and battle tactics performances were historically accurate and great crowd-pleasers. The Friends were proud to provide summer youth employment and, at the same time, provide a living interpretation of history at the Fort. The programme's great success is a testament to Joe's vision and tenacity, together with that of his close colleagues.

As is so often the case with people dedicated to a cause, the Fort reaped the benefit not only of Joe, but also of his partner, Jane Kennedy, and of their entire family who turned out to support events, especially during the years of the Fort York Festival and the labour-intensive parking operation, for more than a decade, that depended on volunteers and employed students working under the hot summer sun and late into the evening. Joe was recognized by the Arts and Letters Club in 2010 when he won their annual award for a non-member making a significant contribution to the arts in Toronto. He retired from the board in 2019.

George Crookshank chest donated to City of Toronto

by Robert Bell Donors Tim and Sue Walker flank their family heirloom – the George Crookshank chest. (Photo by Robert Bell)The City of Toronto has received a generous donation in the form of a very fine antique chest whose original owner was George Crookshank, a colleague and confidant of John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada. Crookshank arrived in York in 1796 and entered the commissary department supplying Fort York and other garrisons in the area. He went on to serve as Assistant Commissary General at Fort York in 1814, Receiver General in 1819, Legislative Councillor (1821-1841), and Director of the Bank of Upper Canada (1822-1827). The Crookshank house was one of the first in York and was famously commandeered and looted during the American invasion of York in 1813 (see Stephen Otto’s “Art as evidence of history: two paintings by Robert Irvine” F&D, July 2018)

Donors Tim and Sue Walker flank their family heirloom – the George Crookshank chest. (Photo by Robert Bell)The City of Toronto has received a generous donation in the form of a very fine antique chest whose original owner was George Crookshank, a colleague and confidant of John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada. Crookshank arrived in York in 1796 and entered the commissary department supplying Fort York and other garrisons in the area. He went on to serve as Assistant Commissary General at Fort York in 1814, Receiver General in 1819, Legislative Councillor (1821-1841), and Director of the Bank of Upper Canada (1822-1827). The Crookshank house was one of the first in York and was famously commandeered and looted during the American invasion of York in 1813 (see Stephen Otto’s “Art as evidence of history: two paintings by Robert Irvine” F&D, July 2018) The Crookshank chest in the dining room of the Officers’ Mess at Fort York. (Toronto History Museums)I was delighted and grateful when Tim and Sue Walker, reached out to me and the Fort York Foundation to express their interest in a possible donation of their treasured heirloom to the City of Toronto. The chest is an oak chest with brass reinforcements designed to hold silverware and two carry handles on the sides. It measures 42 inches L x 28 inches W x 23 ¾ inches H (raised on a 8 ½ inch stand). It dates to 1820-1840 and features an engraved name plate bearing George Crookshank’s name. The reference on the plate identifies Crookshank as “The Hon” and also identifies the location as “Toronto” rather than York. Crookshank was appointed to the Legislative Council in 1821 which gave him the designation of Honourable. Toronto was named York in 1793 and then re-named Toronto in 1834. If the brass plate was attached at the time the chest was created, the Toronto reference suggests the chest dates to c. 1834.

The Crookshank chest in the dining room of the Officers’ Mess at Fort York. (Toronto History Museums)I was delighted and grateful when Tim and Sue Walker, reached out to me and the Fort York Foundation to express their interest in a possible donation of their treasured heirloom to the City of Toronto. The chest is an oak chest with brass reinforcements designed to hold silverware and two carry handles on the sides. It measures 42 inches L x 28 inches W x 23 ¾ inches H (raised on a 8 ½ inch stand). It dates to 1820-1840 and features an engraved name plate bearing George Crookshank’s name. The reference on the plate identifies Crookshank as “The Hon” and also identifies the location as “Toronto” rather than York. Crookshank was appointed to the Legislative Council in 1821 which gave him the designation of Honourable. Toronto was named York in 1793 and then re-named Toronto in 1834. If the brass plate was attached at the time the chest was created, the Toronto reference suggests the chest dates to c. 1834.

Tim Walker is a descendant of George Crookshank and he and his wife, Sue, have enjoyed having the chest for many years at their country home (located very appropriately on Lake Simcoe). Tim and Sue reflected on their decision to donate in Tim’s words below:

“The chest always had a special place in my parents’ home and our homes due to our family history, its beautiful period shape and structure and also its special place in Canadian history. We think it is now more appropriate for the chest to be returned to Fort York where its original owner played an active role in the operation of the Fort.”

Fort York Foundation was pleased to arrange for an appraisal of the chest to facilitate its donation to the City of Toronto in 2021. The chest has undergone conservation and is now proudly on display in the dining room in the Officers’ Mess Establishment at Fort York National Historic Site.

Robert Bell is Executive Director of The Friends of Fort York and the Fort York Foundation.

Relics of the Rebellion of 1837: the money vaults at Fort York

by Carl Benn

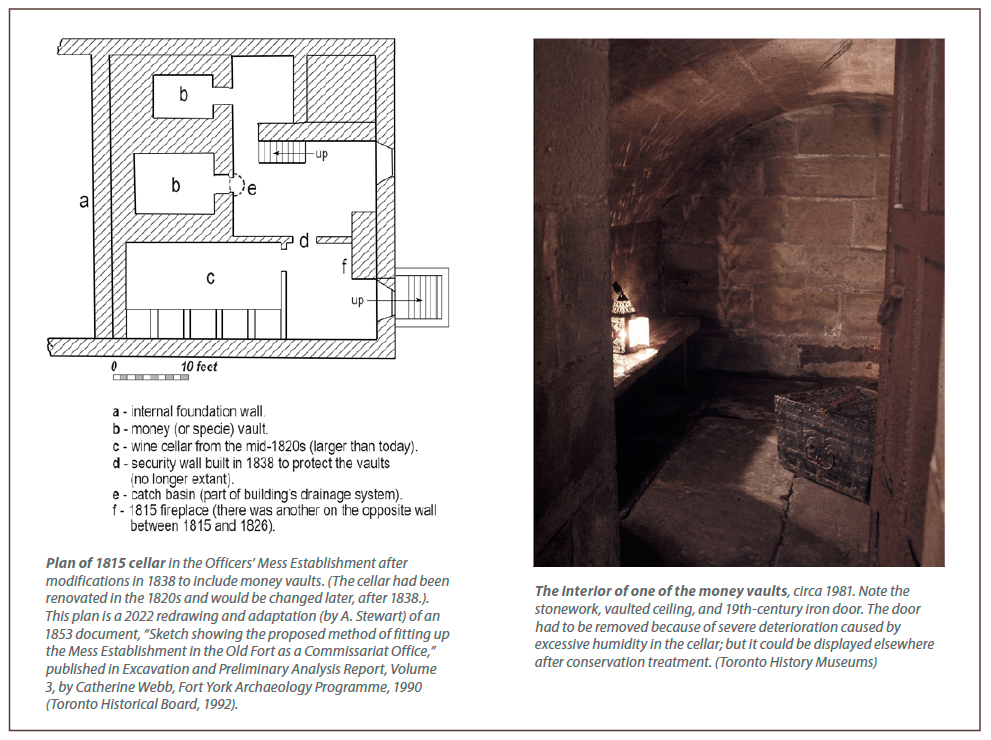

The Bank of Upper Canada on Adelaide St East at George St, circa 1859. (Toronto Public Libraries Digital Archive, Baldwin Collection of Canadiana, PICTURES-R-3103.)Two intriguing architectural relics stand in the Officers’ Brick Barracks and Mess Establishment at Fort York. They are dark, low, cellar rooms that many visitors mistakenly think are dungeons. Instead, they are specie, or money, vaults. They were installed at the end of 1838 to protect bank and army money from guerilla raids on Toronto during the tense aftermath of the Upper Canadian Rebellion.

The Bank of Upper Canada on Adelaide St East at George St, circa 1859. (Toronto Public Libraries Digital Archive, Baldwin Collection of Canadiana, PICTURES-R-3103.)Two intriguing architectural relics stand in the Officers’ Brick Barracks and Mess Establishment at Fort York. They are dark, low, cellar rooms that many visitors mistakenly think are dungeons. Instead, they are specie, or money, vaults. They were installed at the end of 1838 to protect bank and army money from guerilla raids on Toronto during the tense aftermath of the Upper Canadian Rebellion.

A year before, in December 1837, William Lyon Mackenzie marshalled supporters at Montgomery’s Tavern on Yonge Street north of today’s Eglinton Avenue. He intended to take the city, overthrow the government, capture Fort York, and set up a provisional government. Before he attacked, minor skirmishing occurred between his followers and government supporters on 4 December.

As Mackenzie prepared to march, loyalists in the city organized Toronto’s defences as best they could. They had little support from the British army because most soldiers in the province had been sent to Lower Canada where the threat of insurrection was worse. One of the major concerns for Toronto’s loyal citizens was the vast quantity of money in the banks. If the rebels robbed the banks, they not only could finance their cause, but they could threaten the province’s economic stability, already strained by the American financial panic of 1837.

The Bank of Upper Canada alone had £138,000 in gold and silver in its vault along with large quantities of negotiable paper. Loyalists, therefore, recruited a corps of “Toronto Bank Guards” and deployed some of them around the hastily-fortified bank on Duke (now Adelaide) Street, and positioned others at the Commercial Bank of the Midland District on King Street.

On 5 December, Mackenzie led 500-700 rebels down Yonge Street. Other rebels waited in the city, ready to join the rising upon their arrival. However, a small government force led by Sheriff William Jarvis ambushed Mackenzie near today’s Yonge and College streets and sent the rebels retreating back to Montgomery’s Tavern (and those in the city quietly stayed home). More skirmishing occurred on the Sixth. On the Seventh, one loyalist force beat off an assault at the Don River bridge while another dispersed the rebels at Montgomery’s Tavern in a short battle.

Mackenzie escaped to the United States where he attracted both Canadian and American supporters to his cause. These people launched a number of raids into Canada in 1838. Some of the attacks were serious, rivalling War of 1812 engagements. The gravity of the raids, combined with the crisis of the Lower Canadian Rebellion, kept Upper Canada on a wartime footing until the end of the decade.

Within days of the Yonge Street skirmishes, hundreds of loyal Canadian militiamen from the surrounding countryside moved into Fort York while others guarded key points around the city and harbour. The government restored the fort’s deteriorating War of 1812 defences, enlarged its harbour battery, and constructed blockhouses and other defences around the city perimeter. Meanwhile the British army reinforced Upper and Lower Canada substantially (and in the early 1840s replaced much of Fort York’s facilities with the “New Fort” in today’s Exhibition Place).

Yet, the security of bank and government money continued to trouble loyalists through 1838. The banks were a political as well as an economic target. Mackenzie had condemned the banks, describing them as “vile associations” controlled by the colony’s elite. In his denunciations, he singled out the Bank of Upper Canada because of its close association with the government. Mackenzie had gone so far as to promise that there would be no banks in his independent Upper Canada.

While loyalists worried, rebels made a dramatic foray into Upper Canada in November 1838. A force of 250 crossed the St. Lawrence River at Prescott. They hoped to capture Fort Wellington, cut communications between Upper and Lower Canada, and inspire a widespread uprising against the Crown. Once ashore, the invaders fortified themselves at a strong stone windmill a short distance from the fort. Hundreds of British regulars, Royal Marines, and Canadian militia – supported by steam-powered gunboats – counterattacked over several days before the invaders surrendered.

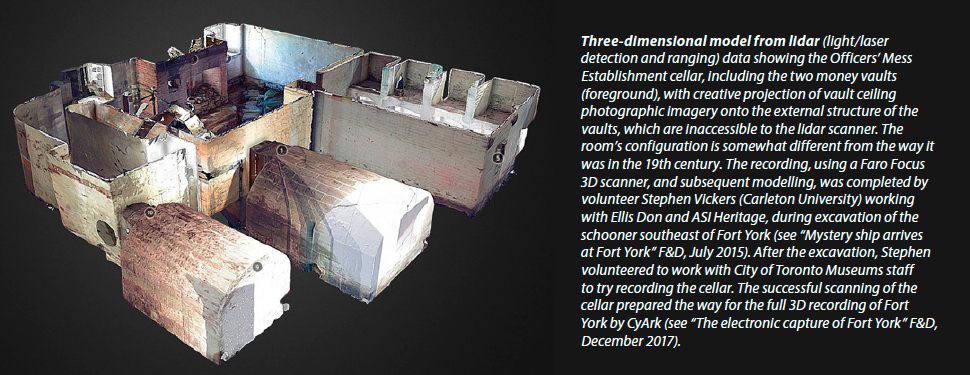

At the same time as the Prescott raid occurred, there were political assassinations in the Niagara area and rumours of invasion in southwestern Upper Canada. Fearful of a widespread uprising, the Bank Guards moved back into position after several months of inactivity. Nevertheless, this did not seem to be enough. The banks – and the army’s money at the Commissariat Office on Front Street – still were vulnerable. Therefore, officials decided to build two vaults inside heavily guarded Fort York as quickly as possible. One was constructed new for the banks. The other was dismantled from the Commissariat Office and reassembled in the fort. Both were located in the 1815 Officers’ Mess cellar. While construction went on in November and December 1838, a worried cashier of the Bank of Upper Canada, Thomas Ridout, sat barricaded inside his office, protected by the Bank Guards. If attacked, he hoped he would be able to hold out until troops from the fort came to his rescue. Ridout must have been relieved when the army finished the vaults towards the end of the year and transferred the money to the fort.

While construction went on in November and December 1838, a worried cashier of the Bank of Upper Canada, Thomas Ridout, sat barricaded inside his office, protected by the Bank Guards. If attacked, he hoped he would be able to hold out until troops from the fort came to his rescue. Ridout must have been relieved when the army finished the vaults towards the end of the year and transferred the money to the fort.

Both vaults were made of thick cut stone and had heavy iron doors to make them fireproof. To improve security, the army constructed a wall between the vaults and a (no-longer-extant) exterior door of the cellar as a second line of defence, and put a heavy lock on an interior door which connected the cellar to the ground floor of the Officers’ Mess. No doubt soldiers were deployed around the building in addition to the force that guarded the fort as a whole.

Eventually, tensions died down and the money vaults fell into disuse in the 1840s. ln the early 1850s, however, the army restored the vaults for the Commissariat, which took over the Officers’ Mess for an office. After the Commissariat left a few years later, the army tore down the security wall in the cellar, but the vaults survived, and may be seen by visitors to the fort today.

While not as romantic as dungeons at first glance, the vaults are fascinating because of their associations with one of the most dramatic periods in the city’s history, and, like many other treasures at Fort York, provide tangible and evocative links to Toronto’s complex past.

This is a revised version of an article Carl Benn wrote in 1995 while Curator of Military History for the Toronto Historical Board. He now is a history professor at Toronto Metropolitan University. We thank Allison Bain, Executive Director of Heritage Toronto, for granting permission to publish this revised version of an article that first appeared in Explore Historic Toronto (issue 8, spring/summer 1995), the newsletter of the Toronto Historical Board (now Heritage Toronto).

Fort York Guard on Pause in 2022

We very much regret to report that The Friends have not been able to obtain support from the City to operate the Fort York Guard this summer. The City has decided to put its relationship with The Friends of Fort York on pause to conduct a review of how closely the values of The Friends currently align with the City’s organizational values and what steps might be required based on the outcomes of the process. The City determined that it was necessary to pause the Guard in the spirit of the review process. A timetable for the process has yet to be announced.

The Guard, consisting of the Squad and the Drums, is a joint and cooperative venture by the City of Toronto in partnership with The Friends of Fort York and has been a popular living history attraction at Fort York. We believe this will be the first time since 1955 that the Guard has not appeared at Fort York in the summer - it will certainly be the first time since The Friends of Fort York took on leadership for mounting the Guard in 1999.

We strongly believe that there is a place for living history alongside the many contemporary events that take place at the Fort. The Guard has provided a welcome and challenging summer employment opportunity for students which, in turn, has attracted support through federal grants. It has also fostered camaraderie and spirited competition with similar groups hailing from other historic forts in Ontario.

The Friends have always appreciated and recognized the intense loyalty and professionalism of the students who have served in the Fort York Guard. The quality of their music and drill demonstrations is second to none. We will hope to see a return of the Fort York Guard in 2023.

If you have views on this subject, please send them to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .